US-Japan: Four key actors in the nuclear drama

Below are profiles of four major players in the 1945 decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- Emperor Hirohito (1901-1989) -

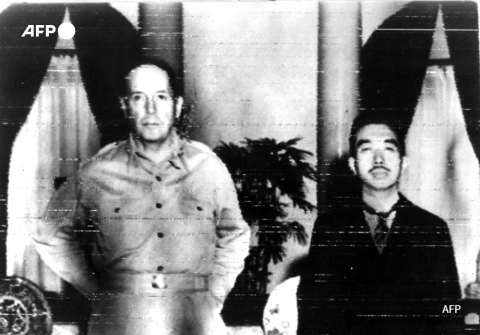

Japanese Emperor Hirohito was regarded as a demi-god and was at the apex of the Japanese state when it waged bloody war across Asia.

Considered to have played a pivotal role in Japan's march to World War II, he was regarded by some as a puppet of an out-of-control military state.

He assumed the throne in 1926 and the imperial army's aggression and atrocities in China began in the 1930s. Japan later formed alliances with Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Historians remain divided to what extent Hirohito supported or condoned Japan's actions.

After the Hiroshima bombing on August 6, 1945, Hirohito continued to "ignore" the Potsdam Declaration that outlined terms of Japan's surrender but did not guarantee the survival of the imperial institution.

It was only after Nagasaki was destroyed that the emperor acknowledged defeat while continuing to insist the formal surrender declaration not contain any demand "which prejudiced the prerogatives of His Majesty as a sovereign ruler".

On August 15 Hirohito addressed the nation by radio to inform it of Japan's capitulation.

While his responsibility for the war remained subject to debate, the US-led occupying force kept Hirohito on the throne to preserve national stability.

He was, however, obliged to renounce his divine status.

The emperor continued to act as a symbol of the nation until his death in 1989, a period that saw the country's transformation from militarism to democracy, with enormous wealth generated by its subsequent economic reconstruction and growth.

- Henry Stimson (1867-1950) -

This US statesman served under six presidents and as US secretary of war from 1940 to 1945 when he was the major decision-maker on the atomic bomb.

Describing it as the "most terrible weapon ever known in American history", Stimson felt that it nonetheless created "the opportunity to bring the world into a pattern in which the peace of the world and our civilisation can be saved."

Along with President Franklin Roosevelt, Stimson fought to obtain the more than $2 billion needed to fund the "Manhattan Project".

Both Roosevelt and his successor Harry Truman followed Stimson's advice on every aspect of the bomb and he overruled the military when necessary, for example by removing the cultural centre Kyoto, which he had visited before the war, from the target list.

Upon Roosevelt's death, it was Stimson who briefed Truman on the bomb's crucial role in the confrontation that lay ahead with the Soviet Union.

- Kantaro Suzuki (1867-1948) -

Japanese prime minister from April 7, 1945, Suzuki was in favour of his country's surrender because of what he considered to be a desperate military situation.

But the admiral of the imperial fleet and former military attache in Germany came up against the army's hardline faction, which was determined to pursue the war at any cost.

Two days after the Potsdam Declaration outlined the Allies' terms of surrender, Suzuki told a July 28, 1945 news conference that Tokyo would "ignore" the ultimatum, which said nothing about the fate of the imperial regime.

Despite the ambiguity of the term used -- mokusatsu, which also translates as "no comment" -- US officials considered it a refusal to capitulate and decided to bomb Hiroshima.

After Nagasaki was destroyed, Suzuki was the target of an assassination attempt several hours before the speech in which Hirohito announced his country's surrender.

- Dwight Eisenhower (1890-1969) -

Convinced that Japan was on the point of surrendering, General Eisenhower, the commander in chief of allied forces in Europe, opposed using the atom bomb in July 1945 when Stimson informed him that a strike was imminent.

"During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings," Eisenhower, who served as president from 1953 to 1961, wrote later.

"First on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary.

"And second because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives."

Stimson did not take account of his views and the bombings went ahead.

Other US military chiefs also opposed dropping the bombs but political and diplomatic arguments concerning the post-war period and a looming confrontation with the Soviet Union outweighed their concerns.