Bombing Hiroshima : 70 years of controversy

by Dominique Chabrol

US President Harry Truman did not hold back on using the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

To do so he had to overrule many US military chiefs who opposed the bombing.

The real motives for the only nuclear strikes in history are still the subject of debate 70 years on.

There is no doubt though that, whether military strategy or "atomic diplomacy", the August 6, 1945 destruction of Hiroshima signalled the start of 40 years of confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Truman, newly inaugurated as president, was clear that the weapon should be used if Japan refused to surrender.

Informed in late April 1945 of the potential of the new weapon, which had been perfected in US laboratories, he ordered that it be prepared for use against Japan after a successful test on July 16 in the New Mexico desert.

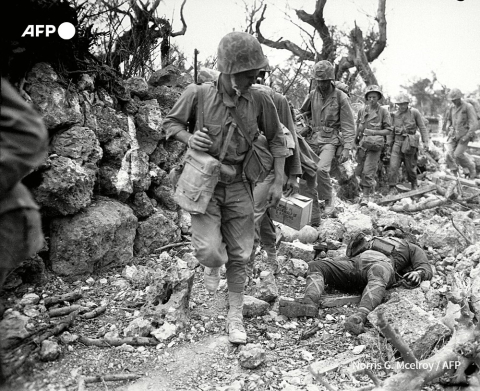

The war in the Pacific had taken four years and the Americans had already lost 100,000 soldiers, including more than 12,000 between March and June 1945 in the Battle of Okinawa.

Japanese kamikaze planes had demonstrated they were prepared to go to any lengths rather than surrender.

Truman believed that dropping the A-bomb would end the war and save the lives of between 500,000 and one million US and allied soldiers, according to Washington strategists.

It would also halt Japanese atrocities against prisoners of war and civilian populations throughout Asia.

But many senior military officials challenged that argument, saying there was no military justification for use of the bomb.

In late April General Dwight Eisenhower, the chief of allied forces in Europe, spoke of his "grave misgivings" when Secretary of War Henry Stimson informed him that a nuclear strike was near.

"First on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary," he wrote later.

"And second because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives."

Top US military officials also pointed to the effect of massive conventional bombings on Japanese cities, which wrought as much damage as could be expected from the A-bomb.

On March 9-10, 1945 at least 80,000 died from US firebombing raids on Tokyo, for example.

- Asserting US power -

But diplomatic considerations also weighed heavily on the US decision to drop the bomb.

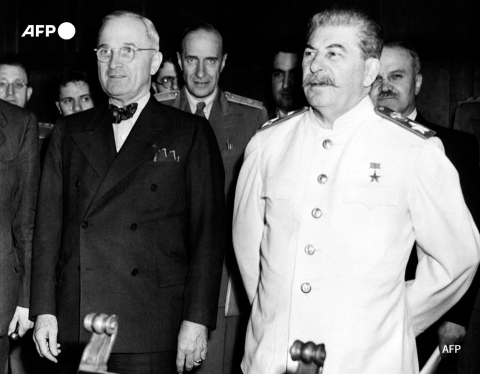

Truman had taken a tougher line with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who had profited from the weakening of his predecessor Franklin Roosevelt during his last months in office to extend Soviet influence in Europe.

The A-bomb thus became a tool to assert US power and put the brakes on the Soviet advance.

For many historians, the Hiroshima bombing signalled the start of a long struggle between the two new superpowers.

"It is difficult not to ask the question: The capitulation signed on September 2 ... was it really the end of a long nightmare or the beginning of the Cold War," said Andre Kaspi, a French specialist in US history.

After the bombing of Hiroshima, which killed 140,000 people by the end of the year, Nagasaki was hit three days later, killing another 70,000.

Newspapers at the time suggested that a desire for revenge formed part of the US decision.

Since the surprise December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the destruction of part of the US fleet, Japan was seen as a treacherous foe with whom any agreement was impossible.

Thousands of US soldiers continued to die every day in the Pacific and the liberation of the death camps in Europe had just revealed the extent of abuses by the Axis powers against civilians.

"Compassion was not the order of the day. Truman did not have any choice," Kaspi said.