Ghana paves the way

Ghana in 1957 became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to achieve independence from a European power, ending more than 80 years as a British colony.

Known as the Gold Coast during colonial times, it was the world's biggest cocoa producer and held major reserves of manganese, gold, diamonds and bauxite.

Britain had opened the way for independence in 1946 by allowing Africans a majority of seats on the legislative council.

After unrest in 1948, it gradually allowed Africans to play an increasingly important role in the colony's administration.

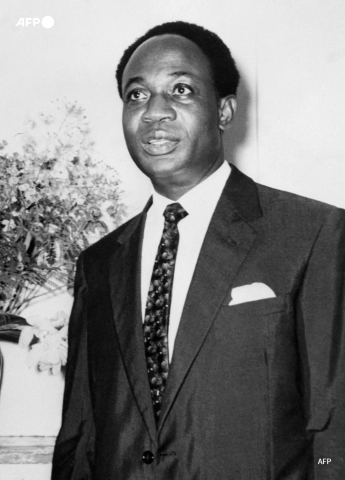

Led by Kwame Nkrumah, who had become prime minister in 1952, the Gold Coast's legislative assembly on August 3, 1956 voted for independence. It was endorsed by the British parliament on December 11, 1956.

Independence came into effect just after midnight on March 6, 1957, when the Union Jack at the Parliament was lowered and replaced by the flag of the new Ghana.

"At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country is free forever!" Nkrumah told the crowds, adding: "Our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent."

Queen Elizabeth remained sovereign until 1960, represented by a governor general. The Duchess of Kent thus opened the first sitting of parliament on the day of independence, as this AFP report recounts.

- First sitting of parliament -

ACCRA, March 6, 1957 (AFP) - Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah and opposition leader K.A. Busia were the first to enter parliament, cheered by their respective supporters.

African and British judges from Ghana's Supreme Court, in crimson robes and white wigs, then took their places and Sir Charles Arden-Clarke was sworn in as first governor general.

Britain's Duchess of Kent read a speech from the throne and a personal message from Queen Elizabeth II in which the monarch said she was thinking of the people of Ghana on this historic occasion.

The prime minister presented an address to the Queen of England, stressing that Ghana ... is proud to be the first African territory to become free and be part of the Commonwealth.

Opposition leader Busia spoke out in support of the speech and paid a stirring tribute to Britain's work in the Gold Coast.

On July 1, 1960 Ghana become a republic with Nkrumah as its president. This AFP report recounts that historic day.

- First day as a republic -

ACCRA, July 2, 1960 (AFP) - Ghana's first day as a republic -- July 1, 1960 -- ended with an evening ceremony in Accra in which President Kwame Nkrumah lit a flame representing "a free Africa".

As the flame rose, he expressed the wish to see Africans handling their own affairs and paid tribute to the millions fighting for their freedom.

The ceremony had started with a parade by a detachment of the Nigerian army to the music of Mozart, accompanied by drums and fifes.

Festivities were closed by a 45-minute firework display, at an estimated cost of more than 3,000 pounds.

In a radio address in the afternoon, Nkrumah had expressed his desire to lead his country towards a socialist-style system.

The lavish nature of the opening ceremony resembled more the proclamation of a sovereign or a religious leader than that of a president of the republic.

Sitting on a golden, winged throne, Nkrumah was handed a solid gold sword presented on a violet velvet cushion by a young pageboy.

As president, Nkrumah imposed a personality cult as the "Osagyefo" (Redeemer). He became a champion of other independence movements on the continent and an architect of "African socialism".

Here is a profile written by AFP's Rene Benezra in 1961.

- Nkrumah, hero of independence -

ACCRA, 1961 (AFP) - Ghana's President Kwame Nkrumah is certainly not the first head of state to have been in prison before coming to power. But he is perhaps the only one to have been plucked out of prison by the authorities to form a government.

In the eyes of his compatriots, his success was something of a miracle, hence the title of "Redeemer" conferred on him last year.

Born in September 1909 in a small village around Axim in the southwest, Nkrumah was the son of a relatively well-off protestant craftsman. He studied at missionary schools before going to a recently founded university at Achimota near Accra.

He decided to become a teacher but a stay in the capital of the then British colony the Gold Coast changed his mind. There he was impressed by a spirited speech by Nnamdi Azikiwe, the future president of Nigeria, in which the elder statesman said Africa needed men who could match -- in terms of education and culture -- their European protectors.

Nkrumah went to the United States to complete his education. He entered Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, which was reserved for blacks, graduating in economy and sociology.

His studies were a means to an end: to serve his country and Africa as soon as possible.

He was quick to throw himself into this venture. Under his leadership, the association of African students of the United States and Canada blossomed, issuing nationalist publications and demands.

He realised, however, that the fight could not be efficiently waged from so far away. He moved to England to support the cause, but was interrupted by World War II. After the conflict ended, he played an active part in the preparation of the November 1945 Pan-African Congress in Manchester which laid down the first practical basis for African solidarity.

(...)

- Return to Ghana -

Returning to Ghana in 1947 after an absence of 12 years, Nkrumah founded the Convention People's Party (CPP) to which thousands of people rallied. His arrest in 1950 and sentencing to prison for revolt and inciting a general strike were a setback. But popular discontent bolstered support for the party and it secured 35 out of 38 seats in the 1951 elections.

Aware of the negative consequences of detaining the leader of the victorious party, the governor pardoned Nkrumah and tasked him with management of government affairs. The following year, in 1952, he became prime minister.

In 1956 Britain agreed to grant independence to the Gold Coast. The territory, to which part of Togo was annexed following a referendum, took the name Ghana.

Nkrumah, at the peak of his glory, coveted leadership of a broader union of African states.

After a preparatory meeting of 11 southern African and Saharan countries in Accra, a follow-up "Conference of Independent African States" discussed the emancipation of territories still dependent on colonial powers, and African unity.

The outcome disappointed Nkrumah, who had hoped for concrete decisions.

Guinea's sudden independence provided him with an unexpected opportunity to further his plan. He proposed a formal union to Guinea's leader, Sekou Toure, who was isolated from the rest of French Africa. The acts of union were quickly signed.

Nkrumah repeated the exercise with Mali when it left its federation with Senegal in 1960.

However leaders in Nigeria, which also secured independence in 1960 and whose population was six times bigger than that of Ghana, were against a union. Africa's francophone leaders were suspicious of Nkrumah's unitarian approach and Liberia's president also remained cautious.

Everything seemed against Nkrumah's aspirations to become African leader.

Using authoritarian measures, he did, however, become the absolute master of Ghana.

He eliminated the opposition, including with a law allowing detention without trial for five years, and secured a vote for a republican constitution with a strong presidential regime.

Accra newspapers published photomontages showing him at the right side of Jesus Christ or walking on the water. The Protestant church saw a danger of emerging "Nkrumahism".

(...)

The religious images disappeared but Nkrumah remained nonetheless the "Redeemer".

As president, he imposed a repressive system under which opposition groups were gagged.

He survived several assassination attempts between 1961 and 1964, and was deposed in 1966 in a military-police coup.

Nkrumah went into exile in Guinea and died in April 1972 in Bucharest, where he was undergoing medical treatment.