Belgian Congo freed in 1960

In the month before it became independent on June 30, 1960, the Belgian Congo -- which became Zaire and then the Democratic Republic of Congo -- was shrouded by uncertainty, with fears of attack in neighbourhoods inhabited by the European colonisers.

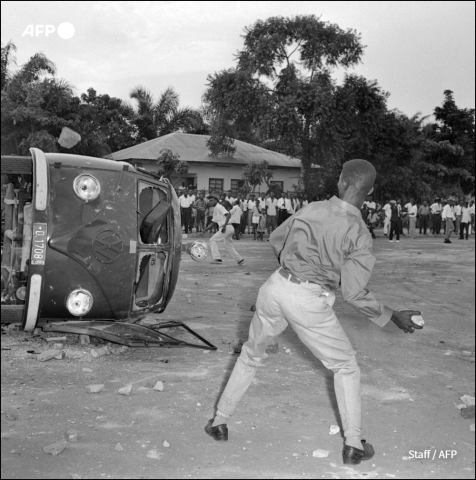

The sprawling central African country was the personal property of Belgian King Leopold II from 1885 until it became a colony in 1908. Violent riots in the capital Leopoldville, which became Kinshasa, led Belgium to grant it independence.

In May 1960 the first legislative elections had been won by the Congolese National Movement of charismatic nationalist Patrice Lumumba, who briefly became independent Congo's first prime minister.

Here are extracts from a report by an AFP special correspondent in the countdown to independence day.

LEOPOLDVILLE, June 5, 1960 (AFP) - The "Palace of the Nation", originally planned to house Belgium's governor general, was finished just in time to accommodate the first Congolese government.

Workmen cut corners as they rushed to get the large riverside building ready for the independence in 26 days' time of the biggest country on the African continent.

In Congo's capital Leopoldville order reigns. Public services are working normally and Belgian officials have been told by the government to remain in place until independence day.

No Europeans have been attacked in the city for the past two months. Troubled until mid-May by tribal infighting which left several dead per fortnight, the vast city of 400,000 inhabitants has been able to sleep peacefully every night since a curfew was imposed.

- Unease -

Notwithstanding, unease weighs heavily. It can be felt in the outlying white neighbourhoods where the many villas abandoned by those who prefer the safety of the city centre are now visited only by burglars.

It can be seen at the airport, where daily flights from Brussels arrive empty and leave packed with women and children, just like in the holiday season.

Belgian national carrier Sabena has from May to July scheduled twice as many flights as normal, carrying 7,000 extra passengers and 80 extra services.

Even that is not enough for the Belgians who want to leave. Tickets have been sold out two months in advance and many who cannot get a seat opt to travel to Rhodesia or Kenya to wait out developments, or elsewhere in Europe by other airlines.

Ships sailing from the port of Matadi are full and warehouses packed with furniture.

The same unease has led the national currency, the Congolese franc, to plummet to three-quarters of its initial value in spite of limits on what can be sent to Belgium, set at 10,000 Belgian francs per bank account and per month.

The Belgians who remain from the 120,000 who had been in Congo, including 30,000 in Leopoldville, say they sleep with a weapon by their side.

- Fears of infighting -

In Leopoldville they feel secure due to the presence of dynamic General Emile Janssens, commander of the capital's "Force Publique". They have less faith in the Congolese troops who will come under his command from June 30.

The Belgians have two main fears over Congo's independence.

Firstly the 15 million Congolese want more than just the vote. With most unable to read, they are looking for immediate benefits like houses and cars.

The Belgians also fear that infighting between tribes from different provinces, or even within the same province, could degenerate into riots of which the whites would be the first victims.

The nationalist Lumumba had played on these fears, predicting an explosion of popular anger if his party were not immediately handed power after winning the May elections.

(...)

On independence day, Lumumba made a virulent speech denouncing abuses by the Belgian colonial powers.

Prime minister of independent Congo from June to September 1960, he was overthrown after just four months in office and put under house arrest by General Joseph-Desire Mobutu.

He was murdered in detention in January 1961, at the age of 35, in a Cold War conspiracy widely blamed on the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Britain's MI6.

Belgium in 2002 expressed "sincere regrets" for its role in the assassination.

"Some members of the government, and some Belgian actors at the time, bear an irrefutable part of the responsibility for the events that led to Patrice Lumumba's death," Foreign Minister Louis Michel told parliament.

- 'Independence Cha Cha' -

A song that commemorates independence in the Democratic Republic of Congo became a popular anthem for the whole African continent. Kinshasa correspondent Samir Tounsi met some of the last surviving musicians behind the "Independence Cha Cha".

KINSHASA, June 29, 2019 (AFP) - In music-loving Democratic Republic of Congo, each June 30 -- the day the country became independent 59 years ago -- is celebrated to the beat of a song that has become the hymn of Africa's dashed hopes: the "Independence Cha Cha".

This monument of musical history is the work of the band African Jazz founded by Joseph Kabasele, who died in 1983.

The group's last two surviving musicians have called for official state recognition, saying they are being left to age in obscurity despite their great musical contribution to the country's culture.

"I do not sing very well," warns former percussionist Pierre Yantula Bobina, the only member of the group still in good health and today a district chief near Kinshasa.

But he does not need much encouragement to hum his group's famous anthem in the Lingala language.

In English, it means: "Independence cha cha, we got it / Here we are free at last / At the round table, we won / Long live 'independence we have won'."

In early 1960 he was, at 18 years old, the youngest of the seven musicians in African Jazz who travelled to Brussels with their instruments.

Their mission: to accompany and entertain the Congolese delegation negotiating independence from Belgium at the Round Table Conference.

The names of key Congolese leaders at the talks are honoured in the song: Joseph Kasavubu, first independence president; prime minister Patrice Lumumba; the Katangese Moise Tshombe.

- 'Symbol of our naivety' -

"See how politics works together with music," says Bobina, who is known as Petit-Pierre, with passion. "Look at the importance of this song."

He thinks it may have been Joseph Kabasele, better known as "Le Grand Kallé", who came up with the famous piece, starting with a few guitar notes even before the talks had begun.

"Kallé predicted the success of the round table," Petit-Pierre says. The lyrics refer to "the independence we grabbed from the hands of the whites. The song urged on the politicians," he adds.

It became a hymn of Africa's emancipation, says prominent writer and academic Alain Mabanckou from Congo-Brazzaville, one of the other 17 African countries that gained independence in 1960.

"Born six years after these independences, I heard 'Independence Cha Cha' in most of the Congolese bars in our neighbourhood of Pointe-Noire," he recalls.

Over time it also became a "symbol of our naivety and insousiance" as hopes for life after independence were dashed, Mabanckou wrote in the French daily Libération in 2010.

There was a misleading belief that "it was enough for the white man to leave for the black continent to resume its his true path," wrote Mabanckou, a critic of African presidents who cling onto power at the expense of their people.

In a cover of "Independence Cha Cha" subtitled "The Day After", Belgian singer Baloji, who is Congolese, expresses the lost hope of the "dawn promises / of a sovereign state / where the ground gives way / between militias and rebels / looting and concealing".

- Copyright claims -

In Kinshasa in 2019 it is another kind of bitterness that Petit-Pierre feels when he arrives at the home of Armando Brazzos, the other only surviving member of African Jazz.

Aged 86, the former bassist is lying on the couch in the living room, sick, silent, absent, despite the unexpected arrival of his friend. He casts a blank look over the old photos on the table.

"Unfortunately the country does not look after our father," says one of his sons, Bob Brazzos Mulema.

A few days before the June 30 independence commemoration, Petit-Pierre told the media that he had sent a letter to President Felix Tshisekedi regretting the musicians' "non-recognition".

"It is in support of my elder who is sick," he sighs, referring to Brazzos.

Petit-Pierre himself is still in good shape despite having a foot amputated in 1963 after a traffic accident that ended his musical career.

The 77-year-old former master of the conga is also claiming copyright on the work of Grand Kallé for the "artists who played at the Round Table".

He is not wealthy. "I am a civil servant of the state, I am waiting for my pension," he says, before boarding a taxi, alone and limping, anonymous in the Kinshasa crowd where half the population is aged under 20.