Nuremberg, the Nazi's symbolic city

The choice of Nuremberg for an historic war crimes tribunal stemmed in large part from its past as a stage for Nazi propaganda but also because its courthouse and prison had escaped being destroyed by Allied bombs.

Adolf Hitler had exploited the symbolic value of the former imperial city as early as 1927, using the birthplace of the German humanism movement as a backdrop for mass rallies to glorify himself.

Once named chancellor, Hitler promised the Bavarian city it would be the Third Reich's "ideological capital."

Albert Speer, an architect among those tried at the post-war tribunal, was given the task of building a monumental complex for the gigantic rallies Hitler had in mind.

He came up with the "Reichsparteitagsgelände" (Nazi Party Rally Grounds), which covered 11 square kilometres (four square miles) and became an icon of national-socialist architecture.

It included the open-air "Leopold Arena", designed to hold up to 150,000 people, a 50,000-seat congress hall modelled after the Roman Colosseum that was never finished, "Zeppelin fields" with wooded areas and man-made lakes, all of which opened onto vast perspectives aimed at making individuals feel insignificant compared with the power of the Reich, and a huge stone tribune from which Hitler could address the people.

From 1933 to 1938, the complex hosted the Nazi's annual party congress, with images taken by the photographer Leni Riefenstahl feeding the regime's propaganda machine.

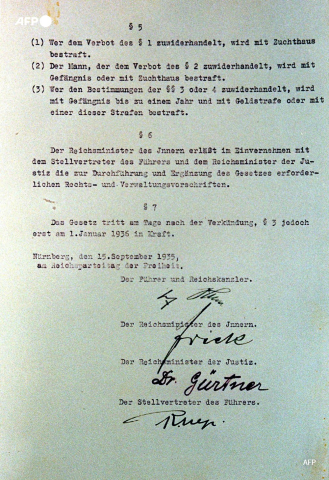

It was during the 1935 congress, on September 15, that the party adopted the landmark Nuremberg Racial Laws.

They included a law on the Reich flag, the Reich Citizenship Law, and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honour, and they integrated the Nazi's anti-Semitic doctrine into the nation's constitutional framework.

Among other things, the third law forbid Jews from marrying or having extramarital intercourse with "citizens of German blood or their relatives", or the employment of German females under the age of 45 by Jewish households.

The citizenship law stated meanwhile that only those of German or related blood could be Reich citizens; all others were state subjects, without citizenship rights.

While the weight of such legislation argued heavily in favour of holding war crimes trials in the city, there was also a practical reason for doing so.

Like most other German cities, Nuremberg was pounded by Allied bombers during the war, and the historic centre was targeted repeatedly in 1945, but the courthouse and a prison linked by a tunnel were still standing, as was the Grand Hotel.

Courtroom 600 is still used for trials today, and the building now also houses the Nuremberg trials museum.

A wing of the "Reichsparteitagsgelände" congress hall is devoted to the Nazi period, with a permanent exhibition entitled "Fascination and Terror."